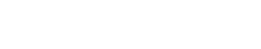

Pictured: Indian Lands in Oklahoma

Oklahoma Struggles with McGirt Decision

Technically, the decision only directly affected McGirt, but the precedent set has created a cloud of uncertainty on the status of criminal law, taxation, and many other matters in lands once held by the Creek Nation. Additionally, it is expected that future litigation will lead to all of eastern Oklahoma which was once held by the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Choctaw tribes being considered Indian land.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court had decided that the Enabling Act of 1906 had created the state of Oklahoma (which joined the Union as the 46th state on November 16, 1907), extinguishing all criminal and civil court jurisdiction of the five tribes often called The Five Civilized Tribes.

As tribal courts are not presently capable of handling the backlog of cases in eastern Oklahoma involving tribal members, it was anticipated that the federal courts would take up the slack. But Doug Horn, senior litigation counsel with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Oklahoma, said that it is estimated that as many as 4,000 cases could be appealed due to the McGirt decision.

Federal prosecutors have refiled 361 cases involving crimes on Creek lands, including 69 murders. Horn said his office only has eight criminal prosecutors, and simply cannot handle the caseload that has been thrust upon them by the McGirt decision. Even if they had the resources to handle all the old cases – not to mention the new cases expected to land in federal court – some cases simply cannot be retried, as some go back to the previous century. Many witnesses have died. Statute of limitations problems will result in no new prosecution in crimes other than murder, and the like, including rapes and shootings.

“I don’t think that [the Supreme Court] realized the magnitude of this decision, and how it affects criminal jurisdiction in eastern Oklahoma, and now it’s going to probably extend to other states and other tribes,” said Muskogee County District Attorney Orvil Loge. Despite using DNA to solve the rapes of five women in Muskogee County, Loge said he had to dismiss the criminal case because the suspect is a member of a federally recognized tribe.

Loge estimates that he has had nearly 500 cases impacted by the McGirt ruling.

Attorney General Mike Hunter has pleaded with Congress to take action to mitigate the problems arising from the McGirt decision. And it is not just criminal matters – as serious as that it is – that are of concern.

The Oklahoma Farm Bureau has also asked Oklahoma’s congressional delegation to do something. Rodd Moesel, the president of the Oklahoma Farm Bureau, wrote, “We recommend Congress enact legislation clarifying that the McGirt decision be limited to criminal jurisdiction under the Major Crimes Act and that it shall not the affect the authority and jurisdiction of Oklahoma, its agencies, counties and municipalities, to regulate civil conduct or civil transactions, to tax, to exercise judicial authority over civil matters, nor shall it enlarge the civil jurisdiction of the Five Tribes, and such authority and jurisdiction shall remain as it existed prior to the decision.”

The Farm Bureau had warned the Supreme Court in a brief filed before the McGirt decision was announced last July that if they sided with McGirt it would “impact [Farm Bureau members] by authorizing tribal taxation or overturning State, county, and municipal taxation of activities and properties; investing tribal courts with broader jurisdiction or divesting State courts of long-accepted authority; and authorizing greater, and potentially, exclusive, tribal and federal regulation over lands, businesses and energy resource development.”

Moesel also expressed concern that the tribes could claim senior water rights, and “limit locations of certain types of agricultural operations by utilizing zoning,” and restrict hunting and fishing on privately owned land within a tribal reservation area.

Gorsuch argued that the predicted dire consequences should not change the interpretation and application of the law, however. He added that he did not believe the ruling will be as consequential as some are predicting. In his decision, Gorsuch said, “(I)t is unclear why pessimism should rule the day. With the passage of time, Oklahoma and its Tribes have proven they can work successfully together as partners.”

He argued, “Congress established a reservation for the Creek Nation ... Though the early treaties did not refer to the Creek lands as a ‘reservation,’ similar language in treaties from the same era has been held sufficient to create a reservation.” Later acts of Congress “leave no room for doubt” that the Creek land was a reservation, Gorsuch contended.

Addressing Oklahoma’s contention that Congress terminated the Creek Reservation during the allotment era, Gorsuch wrote, “Missing from the allotment-era agreement with the Creek ... however, is any statute evincing anything like the ‘present and total surrender of all tribal interests’ in the affected lands.”

“In the end, Oklahoma resorts to the State’s long historical practice of prosecuting Indians in state court for serious crimes on the contested lands, various statements made during the allotment era, and the speedy and persistent movement of white settlers into the area,” Gorsuch continued. But he rejected that this evidence supplied much help to the law’s meaning.

Finally, Gorsuch said that the Enabling Act, which Oklahoma “claims” transferred all non-federal cases pending in the territorial courts to Oklahoma’s state courts to successors to the federal territorial courts’ sweeping authority to try Indians for crimes committed on reservations. That argument, Gorsuch wrote, “however, rests on state prosecutorial practices that defy the MCA, rather than on the law’s plain terms.”

Gorsuch concluded that Congress “remains free to supplement its statutory directions about the lands in question at any time.”

Gorsuch was joined in his decision by Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan.

Writing in dissent was Chief Justice John Roberts, who wrote, “Today, the Court holds that Oklahoma lacked jurisdiction to prosecute McGirt – on the improbable ground that, unbeknownst to anyone for the past century, a huge swathe of Oklahoma is actually a Creek Indian reservation, on which the State may not prosecute serious crimes committed by Indians like McGirt.” Roberts added that the decision has “profoundly destabilized the governance of eastern Oklahoma. The decision today creates a significant uncertainty for the State’s continuing authority over any area that touches Indian affairs, ranging from zoning and taxation” to family law and environmental law.

“Congress disestablished any reservation in a series of statutes leading up to Oklahoma statehood at the turn of the 19th century,” Roberts continued. “Congress began by establishing a uniform body of law applicable to all occupants of the territory, regardless of race ... It abolished tribal courts, hollowed out tribal lawmaking power, and stripped tribal taxing authority .... Finally, Congress made the tribe members citizens of the United States and incorporated them in the drafting and ratification of the constitution of their new State, Oklahoma. In taking these transformative steps, Congress made no secret of its intentions.”

Roberts added that in 1898, the Curtis Act abolished tribal courts in Indian Territory. Then, in 1906, the Enabling Act began the process of joining Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory together in one state, with one judicial system.

Roberts was joined in his dissent by Justices Alito, Kavanaugh and Thomas, although Clarence Thomas wrote a separate dissent, in which Thomas asserted that the Supreme Court had no jurisdictional justification to usurp the jurisdiction of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals. He argued, “Because the Oklahoma court’s ‘judgment does not depend upon the decision of any federal question,’ we have no power to disturb it.” Thomas concluded, “The State of Oklahoma deserves more respect under our Constitution’s federal system.”

Horn said that he hoped the state, federal, and tribal leaders can come up with some sort of certainty soon. Considering that Gorsuch, Roberts, and Thomas issued their decisions in July of last year, and nearly a year later, it is still not clear what is going to happen next as a result of the McGirt ruling, one must conclude that “soon” is not going to happen. In fact, it appears that the full consequences of the McGirt ruling may not be known for years to come.

What is particularly perplexing is the lack of significant action – that can be discerned – on this issue by Oklahoma’s congressional delegation.

Latest Commentary

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025

Thursday 30th of October 2025